A lot has changed since the 2008 Climate Change Act; legally binding carbon budgets have been met by rapidly decarbonising our electricity supply, largely due to significant amounts of PV and wind generation coming online alongside the closure of numerous coal fired generators. However, whilst we have made great progress on electricity, decarbonising heat is proving very difficult and as the fourth carbon budget (2032) sits on the horizon, attention is starting to focus on meeting this.

To meet the demands of the Climate Change Act, nearly all heat in buildings and industrial processes must be decarbonised by 2050. The Clean Growth Strategy (CGS) made it clear that action on decarbonising heat must take place in the 2020s. Partly thanks to the CGS, domestic energy efficiency is also making its way back onto the national agenda, with the imminent ‘boiler plus’, ‘MEES’ the building regulations review and extended ECO to name a few changes.

Stability and smooth transitions are needed

As one of a series of documents following on from the CGS, BEIS yesterday released a call for evidence on ‘A future framework for heat in buildings’.

The call indicates a positive, if small, first step towards action after the RHI closes in 2020 / 2021. Importantly for those in the industry, it includes an acknowledgement by government that regulation is needed to provide clear long-term stability to the industry and consumer post RHI. Aligning with existing policies, BEIS recognise that there must be a smooth transition when the RHI closes (2020/2021), with potential regulation to ensure this “through to the 2030s”. This will aim to reduce barriers whilst also reducing reliance on subsidy (“There may be a role for targeted subsidy…highly targeted in terms of technology it supported, technology it replaced, and the recipient of the subsidy”) and keeping the options open.

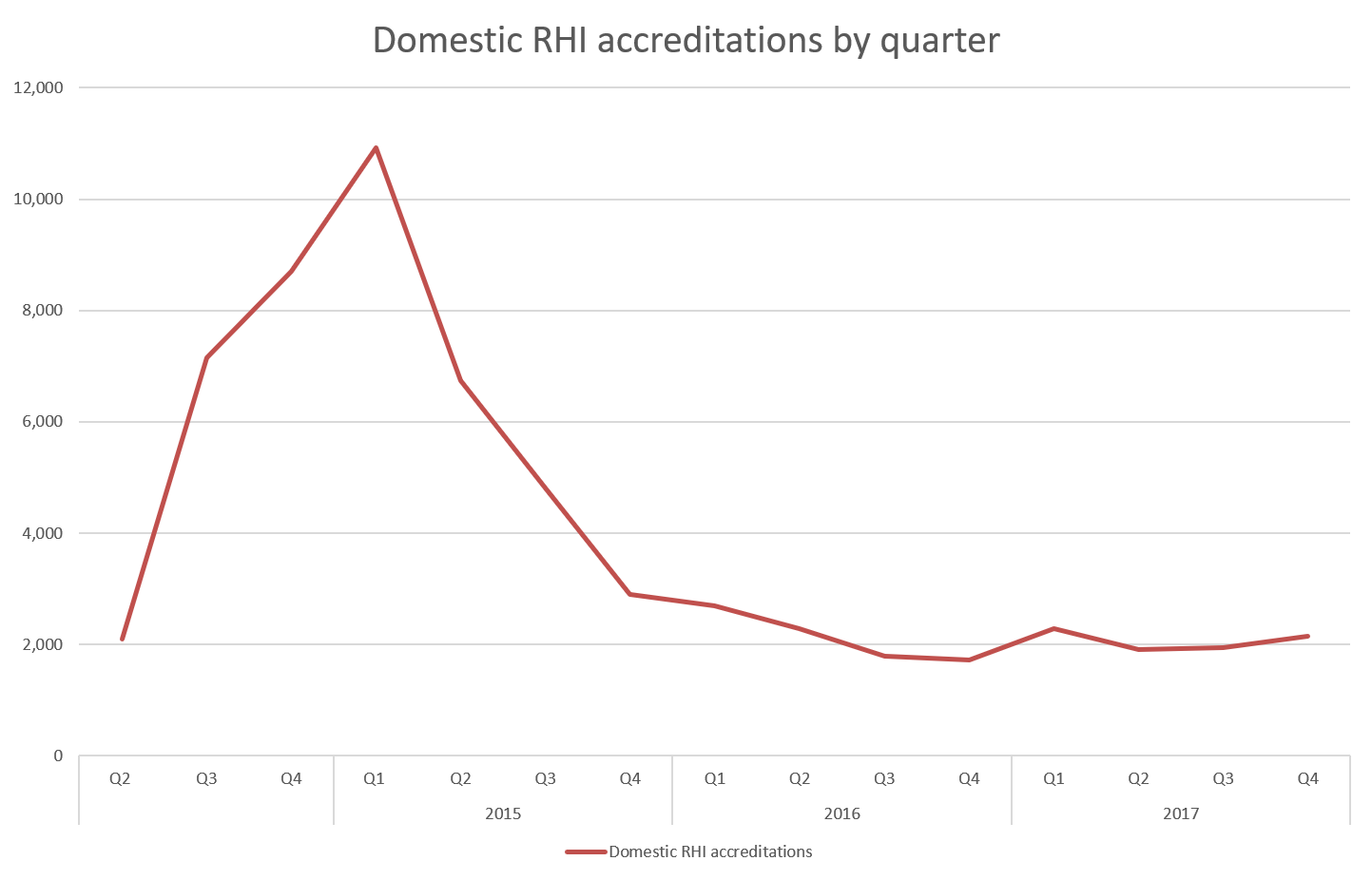

The graph below shows one of the inherent problems with policy to date, an incredibly spiky market, which is sure to compromise quality, ultimately reducing the real carbon reductions made. Avoiding this is key to long term success for all players in this sector.

Which technology?

The domestic RHI has to date been dominated by heat pump (54 per cent) and biomass (22 per cent) installations, predominantly in off-gas areas (76 per cent of installations).

Technologies considered under this call include biomass, bioliquids, biopropane, heat pumps, hybrid heat pumps, gas driven heat pumps, direct electrical heating (storage heaters) and rural heat networks. This signals a recognition that the ‘best’ solution is not yet clear and that other options need to be considered if significant levels of renewable heat are to be deployed.

Heat pumps, predominantly air source, are broadly viewed as the leading solution for decarbonising heat. The idea of shared ground loop GSHPs is also raised on several occasions, recognising the need to address the cost barrier to this more efficient form of heat pump. BEIS is keen for information about hybrid heat pump solutions, their cost and effectiveness.

Biomass will continue to have a role to play in rural off-gas properties that are larger and have limited options for building fabric improvement, but expect it to take a back seat.

Bioliquid and biopropane fuels were previously excluded from the RHI in order not to compete with transport where options for decarbonisation are limited. However, there is a recognition (much championed by OFTEC) that these might have a part to play post-RHI for those difficult to heat buildings that would not be suitable for alternatives such as heat pumps. These are likely to be largely viewed as transition options and there are checks and balances that must be in place to ensure sustainability.

Enabling uptake

Even with the right technology, and some financial support as provided by the RHI, significant barriers to owner occupiers taking up renewable heat remain. This is important as ~17 million of the ~ 28 million homes in the UK are owner occupied.

BEIS identifies the key barriers for this group as: not a priority, adverse to change, lack of knowledge, hassle of installation, perceived complexity, uncertainty over suitability of building, uncertainty over performance, short term occupation of building (not prepared to invest money for long term).

Five near-term regulatory approaches to overcome these barriers are suggested as options:

- Require installers to provide an equal level of information about low carbon alternatives when they quote for a boiler replacement

- A scheme to enable low income and vulnerable households to take up low carbon heating, including building fabric upgrades if required. (Indicated as an arrangement following on from ECO).

- DNOs and GDNs support take up of low carbon heating, by ensuring suitable grid capacity is available and new market solutions such as DSR and other flexibility can be easily accessed.

- Companies producing or selling oil systems are also required to deliver low carbon heating, likely with targets set based on volume of sales

- Oil suppliers are required to sell a certain amount of bioliquid, or renewable heating or pay into a fund that supports low carbon heating installs.

These questions hint at a number of interesting ideas much discussed of late. Are we going to see the ‘traditional’ heating installers pushed into renewables rather than being pulled in?

Could we see the gas and electricity networks playing a more active part in decarbonising heat – perhaps simply by enabling flexibility markets or even installing efficiency or low carbon measures in homes to overcome grid constraints?

Will we start to see heat being sold as a service, like broadband and TV subscription packages, with a third party owning and maintaining the heating equipment?

Can whole house, performance guaranteed approaches such as Energiesprong be delivered at volume and into the able to pay market?

It will be interesting to see how industry responds to the forty four questions posed by this call for evidence, and how that shapes the next ten years of heat.