Kerry Hayes, project manager at Regen, explores the high cost of option fees in leasing Round 4, with the entrance of oil majors in UK offshore wind.

Kerry Hayes, project manager at Regen, explores the high cost of option fees in leasing Round 4, with the entrance of oil majors in UK offshore wind.

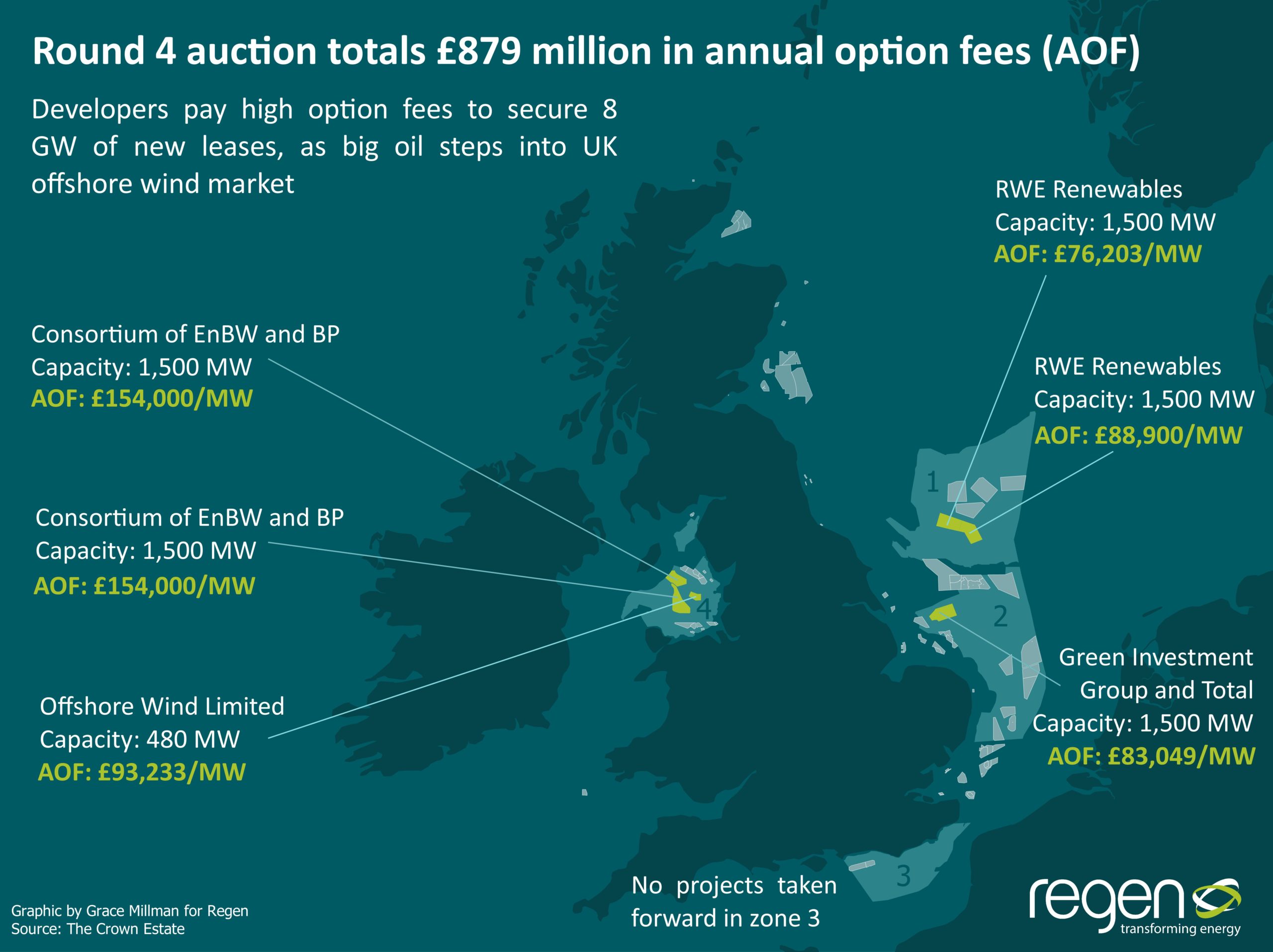

The Crown Estate has now announced the results of the Round 4 leasing round and the winning developers who will take forward six new offshore wind farms (totalling almost 8 GW of capacity) in the waters around England and Wales.

While oil industry companies have for a long time played a major role in offshore wind development (both Ørsted and Equinor, for example, have emerged from the Scandinavian oil and gas sector), this leasing round is notable in the extent to which oil and gas majors have been prepared to throw their weight, and considerable finance, behind winning bids. Multinational BP is probably the most significant new entrant to the UK offshore wind market, being part of a consortium taking 2 leases, totalling 3 GW, in the Irish sea. French oil major, Total (partnering with GIG) picked up a 1.5 GW lease off East Anglia, to add to their existing interests in floating wind as part of the BlueGem project in the Celtic Sea.

Meanwhile, RWE also marked a return to UK offshore wind project development securing 3 GW in the Dogger Bank area, adjacent to their existing Sofia project.

The movement of oil and gas giants into the offshore wind market is not a surprise, as oil companies look to diversify into renewable energy and other parts of the green economy in response to shrinking opportunities in their core fossil fuel sector. It is perhaps more of a surprise that established players, who have driven the success of offshore wind, such as Ørsted, were not part of the winning consortia. It should, however, be remembered that Ørsted (then DONG) did not win leases at the start of the Round 3 processes, instead it picked up projects or partnered with other developers during the long development phase. So, a lot can happen between the award of a lease and the construction of a wind farm and it could be that new entrants will need to partner with experienced developers and construction companies in order to see their projects realised.

The biggest surprise was that the winning option fees offered to secure the leases were so high, perhaps an indication of how attractive offshore wind is as an investment and the anticipation of continued cost reduction, despite the much lower subsidy revenues that are now anticipated through the Contracts for Difference scheme. The high price was also likely the result of the relatively small number of sites made available leading to intense competition between developers.

These option fees are highlighted in this month’s graphic of the month, produced by Grace Millman. Unlike previous leasing rounds, The Crown Estate used an option fee auction, rather than set fixed annual lease payments, leading to developers committing to annual payments of between £82,000 per MW and c.£154,000 per MW. The total sum of these costs, which will be paid to the treasury, is £879 million per year, to be paid annually from the point that the leases are confirmed as seabed rights (which is estimated to occur in 2022) and up until the point the planning consent for the wind farm (typically 4-5 years).

The high price paid is already having an impact across the sector with concerns raised about the sustainability of future projects and the chilling effect on long term competition if oil majors push out more experienced rivals. As a further impact The Crown Estate in Scotland has chosen to reconsider its own leasing round approach, perhaps sensing that there is more value to be extracted from hungry developers.

What happens next will be really important for the development of a sustainable supply chain, new offshore renewable energy generation and for achieving the net zero target. The Crown Estate now need to provide clarity on future leasing rounds to ensure that costs of offshore wind do continue to fall and are not artificially skewed by competitive bidding for a very small number of projects. These Round 4 projects are located in perhaps the last of the “low hanging fruit” sites, within reasonably shallow water and proximity to shore, so it is already likely that the next round of projects will be in more challenging conditions, and so opening up the opportunity for floating offshore wind will also be important in order to capitalise on the progress being made by the Blue Gem project off Pembrokeshire.