The steep fall in the oil price to below $50 a barrel has been the economic story of 2014. We may have hit rock bottom according to the latest statement from OPEC; so now may be a good time, in response to questions from several members, for Regen to consider what impact the oil price fall may have on the outlook for renewable energy.

Predicting energy market trends is of course very difficult and, as the paper below highlights, the impact on renewable energy will depend as much on the next UK Governments energy policies, as it will to how the oil price responds over the medium and long term. Our view however is that while in the short term the fall in oil will lead to increased price competition across all forms of energy generation, a low or even more likely a volatile oil price may well increase the available capital to invest in renewable energy. Indeed there is a thesis that this current price fall heralds a fundamental shift in the energy market which could mark the beginning of the end of oil, and other fossil fuels, as the dominant global energy source.

Immediate impact on renewable energy

The immediate impact has been felt most keenly in the oil industry itself and especially in the already declining North Sea. The reaction of the industry to the current price fall – job redundancies, cancelled investment and cost cutting in the supply chain – which has provided grim reading for oil industry workers over Christmas, suggests that this is not being treated as a price blimp.

Certainly not good news for the UK sector. http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jan/24/scotland-north-sea-oil-sir-ian-wood-snp-independence

Having worked in the industry during an equally difficult period in the nineties, when the last big round of cost cutting and rationalisation drove many UK businesses to the wall, I can well sympathise with my former colleagues. The key thing now is to ensure that the skills and expertise that have been developed in North Sea oil are retained in the UK, and if they are cannot be used in oil they should be transferred too quickly to offshore wind and marine energy.

For renewable energy the oil price fall is a mixed blessing depending what area of impact you look at:

- Access to capital

- Supply Chain effects

- Price substitution

- Price competition

- Subsidy budgets

A key short term positive is that capital which would have been invested in oil and gas is now looking for a new home and renewable energy – which is largely driven by the commitment of governments and communities to tackle climate change and energy security – could now be seen as a safer long term investment. We like to bemoan the uncertainties in our sector but, compared to a 50% price drop, the vagaries of government’s green policies don’t seem so bad. Certainly for those established sectors with big capital requirements such as offshore wind, or potentially tidal lagoons, there is definitely a capital upside.

It’s not just the financial markets that are looking for a new home; we are also seeing a number of industrial and supply chain companies – offshore specialists in particular – looking afresh at the renewable energy sector as a potential growth market. This is one reason why Regen SW and others in the industry have been pressing all UK parties to reaffirm their commitment to renewable energy beyond 2020 to increase investor and business confidence.

This is good news, because access to cheaper capital and increased capacity in the supply chain will be essential if renewable energy is going to meet the other big impact of falling energy prices which will inevitably be increased price competition.

Price competition – more of the same really.

Direct price competition will be felt most keenly in the renewable and energy efficiency sub-sectors for which oil products are a direct substitute – biomass heating, fuel oil and transport for example. One can imagine the urgency being taken out of the decision for some customers thinking about whether to replace that old oil boiler, or whether to invest in the latest fuel efficiency measure. Some reports have suggested that the oil price fall could choke off the fledgling hydro and electric car market.

It’s hard to tell what the direct substitution impacts will be. In the short term some of the heat may be taken out of some markets, but at a strategic level the growth of new technologies such as the electric or hydrogen car is a much longer term trend and will be driven by consumer choice as well as the commitment of governments to reduce emissions.

For renewable electricity the impacts of the oil price fall will depend on the knock-on impact on gas prices and how these are in turn translated into lower wholesale electricity prices.

At the moment the relationship seems to be 50:25:20. A 50% drop in oil price has coincided with a 25% drop in gas prices and a 20% drop in wholesale electricity prices (and a 3-5% drop in consumer bills – “dear big 6 how does that work!”).

In a sense this just means more of the same – a constant need for cost reduction in the renewable energy sector. For the established technologies such as on-shore wind and PV the target must be to get down to the point of price parity, and for offshore wind – through economies of scale, innovation and competition – to get down from a levelised cost of energy (LCOE) of over £150 MW/h to reach the £100 MW/h industry target.

For new technologies and market entrants this will be more of a challenge. An era of continual cost reduction will make it more difficult for new energy technologies to reach commercial scale – unless they are cost competitive – but innovation will still be critical and UK and EU Governments must continue to back technology development with both financial support, fiscal policies and infrastructure.

It comes back to politics (and the treasury)

While price competition amongst energy generators should not be feared, the increasingly ideological politics that surrounds energy is a cause for concern.

It was strange, at times bizarre, that the political jousting that accompanied the rise in energy costs in autumn 2013 (which was clearly caused in large part by the previous rise in oil and gas prices) lead to a vitriolic attack on renewable energy, and even energy efficiency measures, because of their impact on consumer bills. Following such twisted logic one would now expect that the fall in energy bills will allow politicians to support an increased investment in renewable energy and energy efficiency measures.

Well it would be nice to think so, but the reality is that energy, and renewable energy in particular, has become a political football. As former energy minister Charles Hendry put it; when he came to office his goal was to put energy on the front page, by the time he left he wished that it had stayed in the business section.

The immediate battle-lines are likely to be between the DECC and the Treasury, particularly over the workings of the EMR and the allocation of contracts for difference CfD.

Since the subsidy paid under the new CfD scheme is a “top-up” from the market reference price (wholesale price index) to the agreed contract price, the total subsidy paid will increase if the wholesale electricity price falls. Or put another way, the flipside of the government hedging generators against wholesale price volatility, which is a good thing, is that the government’s subsidy budget is now exposed to wholesale price volatility.

This would not be so bad if there was some flexibility in the scheme but DECC is obliged, under pain of death by the Treasury, to ensure that the total subsidies paid under all schemes fall within the overall budget cap within each year of the Levy Control Framework (LCF).

This is a pretty impossible challenge, once contracts are signed the liability is created, and so the only way to limit the LCF budget exposure is to limit the amount of new capacity which is allocated a CfD. Hence the rather paltry amount that has been offered in the current allocation round and the increased uncertainty this has created.

The fall in the oil price has not created this issue but the knock-up impact on wholesale price and the volatility in the market has certainly made it worse. It’s paradoxical that the LCF budget control, which was introduced to limit the impact of subsidies on consumer bills, kicks in most fiercely when consumer bills are falling.

DECC has some budget left under the LCF which it is clearly holding back but we have now reached the point that the LCF budget control is both a limiting factor on industry growth and a cause of great uncertainty for potential investors. One only has to look at the offshore wind sector, with almost 5,000MW of projects with planning consent chasing an estimated 800MW of capacity on offer in the current allocation round, to see that we are at risk of choking off the project pipeline.

DECC must realise this and it is positive that they have announced this week a £25m increase in the allocation pot for Less Established Technologies. Unfortunately this is not enough; given the need to provide an alternative industry to replace the jobs which will be lost in the North Sea, and the ambition to secure inward investment in UK turbine manufacturing and increase UK content generally, there is a strong argument that the next government should use the opportunity of falling electricity prices to increase, and make more flexible, the LCF budget controls

Longer term impacts and the beginning of the end of the carbon century?

Looking at the future of the energy industry the chart definitely says “here be monsters”, but it is interesting perhaps to consider what the oil price collapse may mean for future of global energy markets, and why some commentators are reading in the runes an end to the oil hegemony.

It’s a volatile market

As any trader will tell you the oil price can only go one of three ways – up, down or become more volatile.

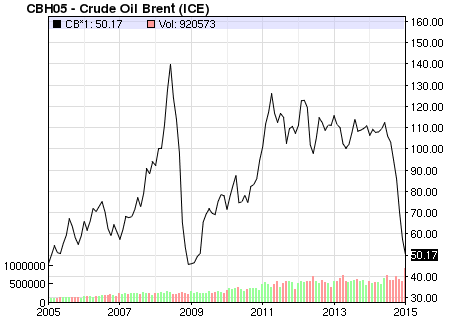

While it’s been a tumultuous period for the oil industry – 6 months ago Brent crude was trading at around $110 per barrel (bbl), now it is down at $50 bbl a fall of over 50% – it is worth highlighting that the sudden fall is not in itself unique. We have been here before; back in 2008/9 oil fell even more dramatically from $140 bbl to under $50. Look a bit further back to the early 1990’s and the oil price was bouncing along at under $20 bbl and regularly dropped below $15 bbl – which was significant because back then that was the baseline threshold for most investment decisions.

1 Source Nasdaq 17/1/2015

Of the current price fall, BP and others are now talking of a low oil price that might last for a minimum of 3 years. Presumably this sentiment is shared by many in the industry hence the immediate response to cut jobs and investment plans.

Proponents of the low price scenario point to the underlying supply/demand imbalance – excess capacity especially in the US and the sluggish growth predicted for world economies.

A lot depends on how long OPEC decides to maintain production levels. Economists are already suggesting that many OPEC producers will struggle to maintain fiscal policies based on oil revenues at price which stays for long below $80 bbl. Against this, the expansion in refining capacity in the gulf states means that key oil producers are also exporting oil products and are slightly less dependent on the crude oil price than they were a decade ago.

A slightly longer term assessment is that after short period of low prices the oil price could quickly recover. The knee-jerk reduction in investment, coupled with an expected recovery in the global economy – plus the usual degree of speculation – has led some commentators to suggest that the next oil price spike in 4 or 5 years could be as high as $200 a barrel.

Of course the oil price has always been volatile – it is subject to shocks from many quarters on both the demand and supply side; economic, political, weather, speculative and logistical. In part this is because oil, and the politics that surround oil, is so critical for our carbon based civilisation. It’s also because the oil supply chain is extremely tight – there is not a lot of slack in the system and surprisingly little storage capacity – if you pump it, you have to move it, you can store it at a price* but eventually you have to sell it. So the oil market is subject to “bull-whip” effects whereby relatively small supply or demand imbalances can produce large fluctuations in the demand and price of commodity materials. As a heavily traded commodity it is also the subject of market speculation, indeed it is increasingly hard to tell what any normalised price of oil should be amongst all the millions of paper trades executed daily.

* Note the charter ranks for oil tankers have shot up in the past months

So what has caused the recent steep decline? And has something changed?

It is an easy bit of analysis to say that the oil market is volatile, but there does seem to be something different about the latest oil price fall.

Industry commentators have identified a number of potential causes and contributing factors behind the latest price fall:

- Global economic downturn – stagnant Europe and slowing growth in China

- America’s shale oil expansion and the US drive for “energy independence”

- Political instability and the need for middle east states to “reassert” themselves

- The burst balloon effect of previous oil price speculation

- OPEC’s stated decision to encourage prices to fall as a means to drive out competition from higher cost producers – shale, deep sea, Arctic drilling etc etc

Causes 1-4 are the usual suspects and have no doubt played their part but they are not entirely convincing and do not explain why the oil industry itself is in such turmoil. Yes there has been a downturn in the global economy but we are not staring at an economic abyss as we were in 2009; US job figures are positive, China’s growth has slowed but it is still expected to grow at an impressive 7.2% on a higher base, India’s is not far behind. European growth is sluggish but we are not in deep recession.

Political instability tends to have a short term impact on oil prices and if anything the politics of the middle east – Arab spring and the conflict in Syria, Iraq and Libya – ought to be pushing oil prices upwards, or at least be encouraging producers to maximise their revenue in order to stave-off political unrest. Certainly it does not look like a good time for a damaging price war.

Point 5, that OPEC has initiated a price war is the more interesting and has long term implications. Whatever the original cause – probably a necessary market adjustment – the oil price has continued to fall because OPEC has taken a decision to maintain production and instigate a period of cheap oil.

This is not to suggest that OPEC has the ability to micro manage the oil price, they have a fairly blunt set of instrument to play with, but there has clearly been a deliberate and calculated shift in OPEC’s strategy.

The stated reason is that OPEC has embarked on a price war is to drive out perceived competition from higher cost producers – shale oil in America, deep sea and new field exploration. Their aim according to some analysts is specifically to take out about 1 million barrels a day of production and to choke off any further investment in new fields in areas like Alaska and the Arctic. Shale oil is particularly vulnerable – most US shale oil producers, with heavy debts and modest balance sheets, generally require a price above $80 per bbl to break even and begin to make their interest payments. Although despite the carnage the US frackers, with relatively low capital costs and short term “pop-up” drilling projects, may be one of the long term survivors in a volatile market if they are able to operate during the good times.

If the oil price collapse heralds a global extinction event it best to be a small borrow living reptile than a big dinosaur out on the plain.

The same is not true of UK fracking, where long planning lead times, environmental risks, decommissioning liabilities and higher capital costs will probably kill off the nascent industry.

Maybe we are not running out of oil? Maybe we are running out of oil demand?

The cause of OPEC’s price war may be competition but the question still remains – why have OPEC taken this decision and why now. As a cartel, whose objective is profit maximisation from the exploitation of a finite resource, it is just not rational to embark on a long term price war. Whatever our western perceptions OPEC is not stupid – they employ the brightest and best economists and analysts to crank the numbers in a shiny office in Geneva. So we must assume that in the long term at least there is a reason and that perhaps something has changed?

OPEC’s aggressive response to see off competition from new producers may have been triggered by the fall in US imports from Saudi to below the symbolic 1m bbl per day and goaded by Barack Obama’s pledge to make the US “energy independent”. If this is the case then we may expect to see a relatively short term fall followed by a recover in oil prices once the market has rebalanced and OPEC producers have made their point. Certainly it’s hard to see that pique at US energy policy alone would hold the cartel together for a long term price war.

The reaction of the OPEC producers and their public announcements suggests that there may be a deeper reasoning at play…….

If you follow the argument that oil is a finite resource and that one day we are going to run out – half gone, peak oil, we will soon see the bottom of the barrel etc – then there is always the option for any oil producer to value the reserve but leave the oil in the ground. Keep the price high to maximise revenue and so what if some high cost freeloaders are able to enter the market.

If however you follow the argument that the world is committed to tackling climate change and will, eventually, stick to the de-carbonisation pledges that have been made at Kyoto, Copenhagen, Lima and (hopefully) this year in Paris, then you could come to the logical conclusion that the only way to do this is to leave oil and other fossil fuels in the ground.

That further fossil fuel development is fundamentally incompatible with decarbonisation was one of the arguments put forward by the Environmental Select Committee’s report of UK fracking.

The issue of “unburnable oil”, “overvalued reserves” and the potential “carbon bubble” has become a hot topic in the last year. A recent study by UCL attempts to quantify this and has estimated that to meet the declared limit of 2c temperature rise would imply that we leave 82% of the remaining coal, 49% of untapped gas and 33% of current oil reserves in the ground.

Now we all might scoff at the idea that world leaders will ever be able to implement such a strategy – and I guess this is the big battleground for climate change over the coming decade – but maybe, just maybe, market forces will lend a hand. A low and increasingly volatile oil price is already likely to choke off investment in high costs fields – see Shell’s withdrawal from the Arctic as just one example. It’s a similar story now for coal. Meanwhile renewable energy has begun to make a significant contribution to the UK’s and global energy mix.

Certainly the likelihood that oil reserves may now be untapped is being taken very seriously by financial bodies like the Band of England as set out in a letter from Mark Carney to the Environmental Audit Committee. The BoE has now widened its study into the financial impact of climate change to consider “stranded carbon assets” and the potential de-stabilising impact of a carbon bubble. It is interesting that the latest marketing campaign by the gas industry – see Statoil – is emphasising that Gas can be part of the low carbon energy mix.

The beginning of the end…….or at least a window into the future?

If the risk of stranded carbon assets is one reason why OPEC leaders are determined to drive out competition and protect market share, then the long term outlook for the oil industry is one of volatility and decline.

The nature of the volatility in the oil market may itself now be changing. Rather than bouncing around a (generally rising) trend line we may see more of the extreme volatility we have experienced since 2009 – periods of investment crushing price falls followed by speculative bubbles. If OPEC, whose role has been to maintain high price stability, now becomes an actor working in the opposite direction then the outlook for the oil industry, and by extension other fossil fuels, becomes even more challenging.

As an aside, the next time someone says that jobs in renewable energy don’t count because they are the result of market distorting subsidies – please point out that the oil industry has been propped up since the 1970’s by the world’s most successful market distorting cartel. It’s an interesting geo-political question – we have fined unscrupulous banks, levied sanctions and broken cartels around the world but no one has ever serious challenged OPEC’s right to fix the oil price.

Perhaps this is stating the obvious; if we are in any way serious about our decarbonisation targets then it must follow that fossil fuel industries will decline over time. What the market turmoil of the last six months gives us is a small window into what that decline might look like:

- Increased market volatility and competition amongst oil producers

- Periodic price falls and speculative price bubbles

- Periodic short term investment and revival in low capital intensive fields – like US Shale Oil

- A reduction in long term investment and the abandonment of high cost fields

- The end of the oil price influence on the overall energy market

- Not with a bang but a whimper decline in market share